Table of Contents

Click here to download the Online Safeguarding Strategy 2021/23 as a PDF

Section One

1. Introduction

“I’ve come up with a set of rules that describe our reactions to technologies:

1. Anything that’s already in the world when you’re born is just normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

2. Anything that gets invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty five is new, exciting and revolutionary and with any luck you can make a career out of it.

3. Anything that gets invented after you’re thirty five is against the natural order of things until it has been around for about ten years when it gradually turns out to be alright really.”

Douglas Adams (1952 – 2001) Author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy

This quote first appeared in the Sunday Times on 29th August 1999

Individuals often associate online safeguarding with Online Grooming and Exploitation, Cyberbullying, Youth Produced Indecent Images and Sexting. However, there is also a much broader and developing agenda particularly in relation to the growth of social media which may include:

- Exposure to inappropriate or harmful material online e.g. gambling content, pornography or violent content

- “Digital” self-harm

- Problematic internet use (internet “addiction”)

- Exposure to content that promotes worrying or harmful behaviour e.g. suicide, self-harm and eating disorders

- Becoming victims of cybercrime such as hacking, scams/hoaxes, fraud and identity theft

- Becoming a perpetrator of cybercrime such as hacking and piracy

- Radicalisation and extremism online

- Publishing too much personal information online

In line with this, online safeguarding is an increasingly common thread running across a number of related and already embedded areas such as child exploitation (CE), anti-bullying, anti-social behaviour and the radicalisation of young people amongst others. If we are to be effective in our approach, it is essential that colleagues across all related agendas work together cohesively to ensure a common and collaborative approach and ensure the online aspects are appropriately reflected in related risk areas.

As is apparent, the scope of online safeguarding is significant. However, for the purposes of clarity in the context of this Strategy, Online Safeguarding is defined as:

A SAFEGUARDING INCIDENT WHERE TECHNOLOGY IS INVOLVED.

"Children and young people need to be empowered to keep themselves safe. At a public swimming pool we have gates, put up signs, have lifeguards and shallow ends, but we also teach children how to swim."

Dr Tanya Byron, Safer Children in a Digital World (2008)

Educating children and young people (and those adults who support them) on how to recognise the potential risks whilst online and how to deal with them appropriately, should form the core of an effective online safeguarding strategy. Online safeguarding is first and foremost a Safeguarding issue and when broken down into its constituent elements and areas of risk, is fundamentally concerned with behaviours. It is therefore important that we are not side-tracked into thinking online safeguarding is an Information Communication Technology (ICT) issue or that technical measures are the solution to the issues. Whilst ICT has an integral part to play in contributing to the safeguarding of our children and young people, the ICT itself is incidental to the issue.

The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Children Partnership Board (CPSCPB) recognise the need for concerns of Online Safeguarding to be recognised and addressed. The CPSCPB has the following vision –

“To empower children, parents, carers and professionals to safeguard themselves in the digital world”

Research from EU Kids Online found

- The more children use the internet, the more digital skills they gain, and the higher they climb the ‘ladder of online opportunities’ to gain the benefits.

- Not all internet use results in benefits: the chance of a child gaining the benefits depends on their age, gender and socio-economic status, on how their parents support them, and on the positive content available to them.

- Children’s use, skills and opportunities are also linked to online risks; the more of these, the more risk of harm; thus as internet use increases, ever greater efforts are needed to prevent risk also increasing.

- Not all risk results in harm: the chance of a child being upset or harmed by online experiences depends partly on their age, gender and socio-economic status, and also on their resilience and resources to cope with what happens on the internet.

- Also important is the role played by parents, school and peers, and by national provision for regulation, content provision, cultural values and the education system.

Young people are often perceived as having a greater knowledge and affinity with technology than many adults. However, it does not follow that they also possess the broader wisdom or emotional maturity adults have developed through life experience. It is therefore vital that we encourage them to increase their understanding of the potential hazards technology presents, developing their resilience and how they can help to mitigate the risks to them (and to others) through their behaviour. It is also clear that parents and carers naturally have a fundamental influence on their children’s behaviour and as such, have a critical role to play in embedding what is acceptable and unacceptable behaviour online (particularly in relation to the use of social media) and therefore, developing parent/carer awareness and confidence around the online environment is a key priority.

As adults, we will understandably take a perspective of ‘responsibility’ but it is essential that we retain a ‘child-centric’ view when approaching the safe use of technology and appreciate how children and young people perceive the risks and the enormous part that technology will play in their lives. Research informs us that issues often go unreported by young people for a variety of factors including: a fear of being held to blame; losing access to the technologies they treasure or simply from embarrassment. If we are to address this issue effectively, we must raise awareness and develop the confidence in utilising the support routes available to children and young people including their own school support mechanisms, CEOP’s Report button and ChildLine.

The prevalence of online messaging, social networking and mobile technology effectively means that children can always be ‘online’. Their social lives, and therefore their emotional development, are bound up in the use of these technologies. We can no longer adequately consider the safeguarding or wellbeing of our children and young people without considering their relationship to technology – we can no longer seek to support and protect them without addressing the potential risks which the use of these technologies poses.

Whilst the focus of this online safeguarding strategy surrounds the safeguarding of our children and young people, members of the children’s workforce must also be aware of the issues. This includes the standards expected in relation to their own use of technologies such as social media, both within and outside of the work environment. Equally, professionals must also be aware of the potential for online abuse towards them by other users and the options available to them should this occur but also the possibility for professionals to behave inappropriately towards other users which also constitutes abuse.

Definition of Online Safeguarding?

‘Online Safeguarding’, ‘Online Exploitation’, ‘eSafeguarding’, ‘Internet Safety’, ‘eSafety’, ‘Digital Safeguarding’ and ‘Online Safety’ are all interchangeable terms used to varying extents. However, regardless of the term used, all should relate to ensuring children and adults using technologies both now and in the future do so safely and responsibly.

Key Themes and Issues

The most recent research and statistics have identified the following:

- 30% of 5 to 7 year olds, 44% of 8 to 11 year olds and 87% of 12 to 15 year olds use social media apps/sites. 4 in 10 children reported using social media sites before reaching the minimum age requirement

- 1 in 3 children reported having seen online content that they considered worrying or nasty

- Around 3 in 10 young people have been bullied online, 38% was through online games

- More than 50% of 12 to 15 year olds experienced ‘hateful content’ as anything that had been directed at a particular group of people based on, for instance, their gender, religion, disability, sexuality, or gender identity.

- 3 in 4 parents felt they knew enough to help keep their child safe when online. have looked for or received information or advice about how to help their child manage online risks

Between 1st April 2012 and 31st December 2020, Police in England and Wales have recorded more than 25,000 sexual grooming offences, 365 of which were across Cambridgeshire and Peterborough[1]

Between 1st April 2012 and 31st December 2020, Police in England and Wales have recorded almost 150,000 offences involving Obscene publications, almost 2,000 of which were across Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. [2]

In just 60 seconds, an extraordinary number of data is generated across the web, and COVID-19 has made that number rise dramatically.

What are the Risks?

Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE)[3] places a significant emphasis on Online Safety and firmly embeds the issue within the broader Safeguarding agenda. The focus on the responsibilities for Schools and Colleges are broad and have substantial implications for how Governors and Proprietors must ensure effective Online Safety provision is in place. As highlighted in the statutory guidance, “…the breadth of issues classified within online safety is considerable, but can be categorised into three areas of risk:”

Emphasising the increasing importance of Online Safety, KCSIE includes a dedicated section (Annex C), highlighting the three areas (3C’s) as:

Content: being exposed to illegal, inappropriate or harmful material; for example pornography, fake news, racist or radical and extremist views;

Contact: being subjected to harmful online interaction with other users; for example commercial advertising as well as adults posing as children or young adults; and

Conduct: personal online behaviour that increases the likelihood of, or causes, harm; for example making, sending and receiving explicit images, or online bullying.

The table below illustrates these categories as a matrix grid identifying examples under headings of Commercial, Aggressive, Sexual and Values. It is important to remember that there is overlap between some of these categories and boundaries are sometimes blurred.

| Commercial | Aggressive | Sexual | Values |

Content (Child as recipient) |

|

|

|

|

Contact (child as participant) |

|

|

|

|

Conduct (child as actor) |

|

|

|

|

Areas of Risk based on Safer Children in a Digital World: The Report of the Byron Review

As both the technology and the behaviour of individuals change, these risks will also develop. Therefore, if we are to ensure an effective approach, our Strategies and Policies must be equally robust and regularly reviewed to ensure currency.

Although the grid has been defined in terms of ‘child’ use, it is relevant to everyone who uses digital and mobile technologies

Links with Mental Health

There is a “clear association” between the amount of time spent online and mental health problems, particularly depression, poor sleep quality and other social and emotional problems. The concept of the ‘Fear of Missing Out’ (FoMO) has been robustly linked to higher levels of social media engagement which has been known to cause distress in the form of anxiety and feelings of inadequacy when they are not online.

Children, particularly around the time of adolescence can become obsessed with ideas about themselves and their lifestyle. With smartphone cameras, and online filters and image-manipulation techniques, there has been a rise in the popularity of ‘selfies’. This has led to concerns about the abundance of idealised images of beauty on social networks and the impact this has on young people’s view of their own appearance.

It has been found that young people can access harmful information on the internet or make connections with people online who encourage them to self-harm. For example, some websites imply that unhealthy behaviours, such as anorexia and self-harm, can be normal lifestyle choices. Social networking also provides the opportunity for online groups to form that promote these unhealthy behaviours.

There have been a number of high profile cases involving cyber-bullying and suicides over the past decade and reports of suicide clusters facilitated by social media. It is very easy to find pro-suicide information, such as detailed information on methods, on the internet. Another concern is the risk of ‘contagion’ where young people are encouraged to take their own lives after witnessing others describing suicidal thoughts or leaving suicide notes on social media. More recently, there have been several reported incidents of young people livestreaming suicides on social media. Research on the internet and self-harm amongst young people found that while young people most often use the internet to find help, there is the risk that the internet can normalise self-harm and discourage young people from talking about their problems and seeking professional help.

Digital self-harm, as it has been termed, occurs when an individual creates an anonymous online account and uses it to publicly send hurtful messages or threats to one’s self. Digital self-harm is defined as the “anonymous online posting, sending, or otherwise sharing of hurtful content about oneself.” Most commonly, it manifests as threats or targeted messages of hate – the more extreme and rare forms of cyberbullying.

If professionals become aware that a child or young person appearing to be accessing online content of this type this should be raised with relevant others, including the safeguarding lead in their organisation, to ensure this information is shared appropriately and that support can be put in place.

Our approach

Local Safeguarding Arrangements have a statutory duty to safeguard and promote the welfare of children and young people. The Safeguarding Partners objectives are to coordinate what is done by each person or body represented to safeguard and promote the welfare of children and ensure the effectiveness of that work. Traditionally this has referred to the ‘real’ world but increasingly children are also living in a ‘digital’ world. We therefore have to adapt our thinking to include new technology and means of communicating and develop approaches to encompass the digital world.

This approach will need to have several strands and will need to focus on work with children and young people, their parents and carers, and the professionals who work with children and young people. Whilst we must understand the issues and risks posed, we must be careful not to demonise the technology and ensure that these are balanced with the immense opportunities and benefits that new technologies bring.

Managing and mitigating these risks strategically is most appropriately addressed by ensuring we maintain a holistic overview. However, in order to tackle the issues effectively, we must break them down into practical areas to be addressed. As such, the framework used for this Strategy is developed from the original and widely-recognised ‘PIES Model for limiting eSafety Risk’. This model quantifies Online Safeguarding into four inter-related areas.

Policies and Practices – To support and ensure stakeholders develop and maintain robust and effective policies, practices and procedures to safeguard children and young people against online risks

Infrastructure and Technology – To identify and promote technologies, tools and infrastructure services which are carefully monitored and which appropriately support online safeguarding priorities for children and young people and related stakeholders

Education and Training – To promote and support effective learning opportunities for all stakeholders which recognise and address current and emerging online safeguarding risks for children and young people

Standards and Inspections – To monitor online safeguarding arrangements and incidents to enable professionals to respond to, manage and support children, young people and families experiencing online concerns

Online Safeguarding Audit Tool

The Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Partnership Board have produced an Online Safeguarding Audit Tool[4] for organisations to evaluate risks, strengths and weaknesses and the extent to which the organisation is meeting requirements to manage and reduce online abuse and where there may be action points for future improvement. It is expected that all agencies that have a statutory requirement to safeguard children and young people should undertake the self-audit every 2 years and submit to the Safeguarding Partnership Board for monitoring, challenge and evaluation.

Audience

The range of individuals, groups and organisations with a responsibility for safeguarding our Children and Young People is significant, ranging from Parents / Carers through to Local and National Government bodies. As such, this Strategy is primarily aimed at (though not limited to) those groups identified below.

- All Agencies represented on the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Children Partnership Board

- All Education establishments (including maintained schools, independents and academies) and Early Years settings across the county

- 3rd Sector organisations, including Voluntary, Community and Faith Sectors

- Private and public-sector organisations providing support, guidance and/or training to stakeholders

- All providers delivering services to/for children across the county

- All private and public sector Service providers delivering technical services and points of access utilised by our Children & Young People

Governance

Governance is provided by the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Children Partnership Board.

All Board members are responsible for implementing and embedding this strategy within their own agency and the Safeguarding Children Partnership Board will hold members to account over this.

Section Two

Agency and professional responsibilities:

Responsibility of all agencies

No single agency is able to address the complex elements of Online Safeguarding on its own, largely because a child’s and family’s needs cannot always be met by a single agency. Effective interventions, whether early help, child in need or child protection depend on professionals developing working relationships which are sympathetic to each other’s legal responsibilities, agency’s purpose and procedures respective roles and agencies capacities.

All agencies represented on the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Children Partnership Board have a responsibility to contribute to the safeguarding of children across Cambridgeshire and Peterborough. Roles and responsibilities are clearly defined in both statutory guidance and the CPSCB Procedures and include the following:

- To view the safety and wellbeing of children as paramount.

- To ensure that achieving the best outcomes for the child is the primary focus when working with Online Abuse.

- To ensure that their workforce understand the significance of all types of abuse against children both in the ‘Real World’ and the ‘Digital World’ and equip their workforce to work effectively in situations where Online Abuse is a feature. This includes staff understanding the links of Online Abuse with other types of abuse particularly Child Sexual Abuse.

- To share relevant information and collaborate with other agencies and work together to ensure accurate assessments and the early identification of needs.

- To harness and develop resources to ensure that interventions are proportionate, effective, and delivered sufficiently early so as to reduce the likelihood of any escalation of adversity for the child.

- To ensure that staff attend CPSCPB training on all elements of abuse and that the training is embedded in practice.

Responsibility to share information

Information sharing is essential to enable early intervention and preventative work, for safeguarding and promoting welfare and for wider public protection.

It is important that practitioners can share information appropriately as part of their day-to-day practice and do so confidently.

It is important to remember there can be significant consequences to not sharing information as there can be to sharing information. You must use your professional judgement to decide whether to share or not, and what information is appropriate to share.

Data protection law reinforces common sense rules of information handling. It is there to ensure personal information is managed in a sensible way.

It helps agencies and organisations to strike a balance between the many benefits of public organisations sharing information, and maintaining and strengthening safeguards and privacy of the individual.

It also helps agencies and organisations to balance the need to preserve a trusted relationship between practitioner and child and their family with the need to share information to benefit and improve the life chances of the child.

Please see the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Safeguarding Children Partnership Board Effective Support for Children and Families (Thresholds) Document for more information.

Identifying online abuse:

The following information is aimed to help professionals in considering and recognising possible cases of Online Abuse.

Online abuse relates to (but is not limited to) the use of technology to manipulate, exploit, coerce or intimidate a child to:

- Engage in sexual activity;

- Produce sexual material / content;

- Look at or watch sexual activities;

- Behave in sexually inappropriate ways or groom a child in preparation for sexual abuse either online or off-line.

It can also involve directing others to, or coordinating, the abuse of children online.

As with other forms of sexual abuse, online abuse can be misunderstood by the child and others as being consensual and / or occurring without the child’s immediate recognition or understanding of abusive or exploitative. In addition, fear of what might happen if they do not comply can also be a significant influencing factor.

Financial abuse can be a feature of online abuse, it can involve serious organised crime and it can be carried out by either adults or other children.

Online abuse can also include cyber or online bullying. This is when a child is tormented, threatened, harassed, humiliated, embarrassed or otherwise targeted by another child using the Internet and/or mobile devices. It is often behaviour between children but could potentially include adults, it is also possible for one victim to be bullied by many perpetrators. In any case of severe bullying it may be appropriate to consider the behaviour as child abuse by another young person.

The internet can be used to engage children in extremist ideologies. A child or young person may also use the internet to reinforce unhealthy messages /ideation such as suicide and eating disorders.

It is important to remember that no child under the age of 18 can consent to being abused or exploited.

Many of the signs that a child is being abused are the same no matter how the abuse happens.

A child may be experiencing abuse online if they:

- spend lots, much more or much less time online, texting, gaming or using social media

- are withdrawn, upset or outraged after using the internet or texting

- are secretive about who they’re talking to and what they’re doing online or on their mobile phone

- have lots of new phone numbers, texts or e-mail addresses on their mobile phone, laptop or tablet.

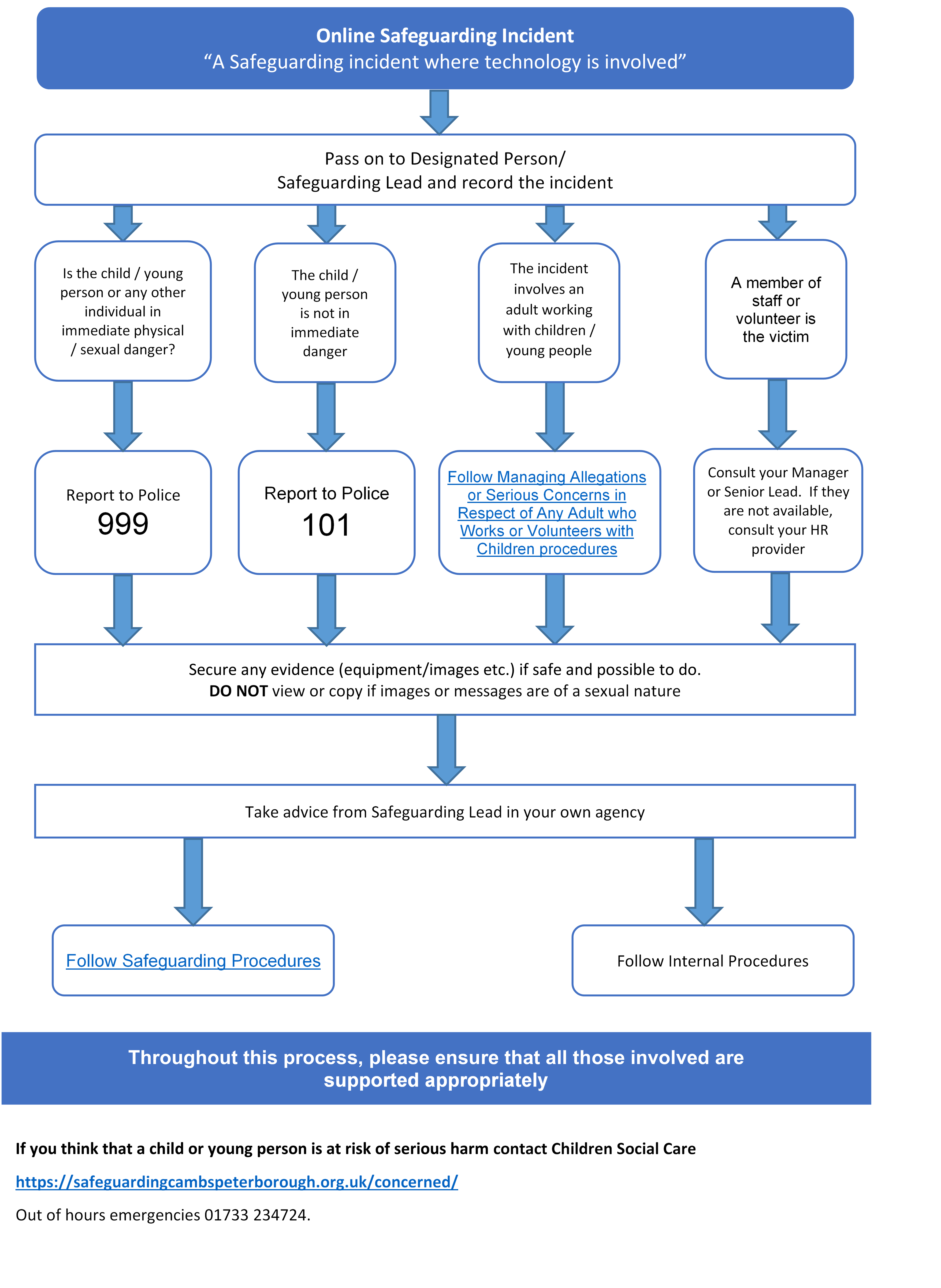

Online Safeguarding Incident Flowchart and Guidance notes

Definition of an Online Safeguarding incident – “A Safeguarding incident where technology is involved.”

Designated Person or Safeguarding Lead

All teams/organisations should have a named person who manages child protection concerns.

Anyone who becomes aware of an online safeguarding incident should record the facts and information as for any other Child Protection concern. This should be passed on to the Designated Person or Safeguarding Lead. Where a child is deemed to be at risk of significant harm a referral to Children’s Social Care must be made. The local Safeguarding Partnership Board Effective Support for Children and Families (Thresholds) Document can support in the level of support that may be required.

It is not possible here to list all of the possible offences that can be committed in relation to technology and safeguarding. All staff should therefore consider whether the child/young person or other individual is in immediate danger that requires a police response.

Secure evidence

- Take all necessary steps to stop the device from being used – if it is safe and possible so to do.

- Do not delete any evidence e.g. images, messages – Ensure that child is not at risk of further abuse. This might mean removing a device. If able ensure device is placed in a secure place so evidence cannot be destroyed or child further abused.

- Do not copy any evidence e.g. images, messages etc as you may be committing an offence.

- Write down what has been seen or sent in accordance with normal child protection procedures.

Member of staff or volunteer is the victim – this may include:

- Cyberbullying – threats, harassment, defamation of character etc

- Posting of slanderous material

- Creating a bogus Facebook page

Managing Allegations or Serious Concerns in Respect of Any Adult who Works or Volunteers with Children

The LADO will give further advice as necessary if an online safeguarding incident involves an Adult who works or volunteers with children.

| For Peterborough | For Cambridgeshire |

Tel: | 01733 864038 | Tel: 01223 727967 |

Email: | ||

Procedures: | http://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/children-board/procedures/managingallegations/ | |

Multi-agency Safeguarding Procedures can be found at the following links – http://www.safeguardingcambspeterborough.org.uk/children-board/procedures/

The flowchart and guidance refer to various posts within an agency or organisation. Each different agency and organisation will need to determine within their own structure who the relevant officers are.

You come across a Safeguarding concern involving technology …

Responding to Concerns About the Safety of Children and Young People Online

When there are concerns about the welfare of a child due to activity which has occurred online then the agency should use its usual safeguarding children procedures and good practice to respond to these. In this sense the context of the abuse / harm occurring online is no different to other situations where there is a concern about a child’s welfare.

If there is a concern about actual Significant Harm or the risk of Significant Harm to a child arising whist online then the agency should immediately activate its own safeguarding children or child protection procedures, and make a referral to Children’s Social Care – see Making Referrals to Children’s Social Care Procedure. Again this is no different to concerns in other situations. If a child or young person is in immediate danger then contact the Police on 999.

When an incident raises concerns both about Significant Harm and unacceptable use, the first and paramount consideration should always be the welfare and safety of the child directly involved.

Legal Framework

Crimes involving indecent images of children fall under Section 1 of the Protection of Children Act 1978, as amended by Section 45 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003 to extend the definition of children from under 16s to under 18s. It is illegal to take, make, permit to take, distribute, show, possess, possess with intent to distribute, or to advertise indecent photographs or pseudo-photographs of any person below the age of 18. Allowing or encouraging a child to view adult pornography, and/or extreme forms of obscene material is illegal and should warrant further enquiry.

The Serious Crime Act (2015) introduced an offence of sexual communication with a child. This applies to an adult who communicates with a child and the communication is sexual or if it is intended to elicit from the child a communication which is sexual and the adult reasonably believes the child to be under 16 years of age.

The Act also amended the Sex Offences Act 2003 so it is now an offence for a person (A) over the age of 18 to meet intentionally, or to travel with the intention of meeting a child under 16 in any part of the world if they have met or communicated with that child on at least one earlier occasion, and intends to commit a “relevant offence” against that child either at the time of the meeting or on a subsequent occasion. An offence is not committed if (A) reasonably believes the child to be 16 or over.

Online Grooming

Online grooming is when someone builds an emotional connection with a child or young person online to gain their trust for the purposes of Sexual Abuse, Sexual Exploitation or Trafficking. This can be a stranger or someone they know such as a friend, a professional or family member, a female or male, adult or peer.

Groomers can use social media sites, instant messaging apps including teen dating apps, or online gaming platforms to connect with a young person or child. They can spend time learning about a young person’s interests from their online profiles and then use this knowledge to help them build up a relationship or send messages to hundreds of young people and wait to see who responds.

Groomers can easily hide their identity online and pretend to be a child, then become ‘friends’ with children they are targeting. Sexual Abuse means a child or young person is being forced or persuaded to take part in sexual activity; this doesn’t have to be physical contact, it can happen online. Increasingly, groomers are sexually exploiting their victims by persuading them to take part in online sexual activity. Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology. Abuse is possible in real time using webcams to provide material for paedophile groups.

Often children and young people don’t understand that they have been groomed or that what has happened is abuse.

The impact on a child of online-based sexual abuse and exploitation is similar to that for all sexually abused children. However it has an additional dimension of there being a visual record of the abuse. Online-based sexual abuse of a child constitutes significant harm through sexual and emotional abuse and Child Protection procedures should be followed accordingly.

In addition to grooming a child to physically meet up with them at a location where contact abuse can occur, this may include but is not limited to:

- Distribution of indecent photographs/pseudo photographs (images made by computer graphics, or other means, which appear to be a photograph) of children;

- Encouraging a child to behave in sexually inappropriate ways or engage in sexual activity;

- The production and distribution of abusive images of children (although these are not confined to the Internet);

- Where a child or young person is groomed for the purpose of Sexual Abuse (online or offline);

- Where a child is exposed to sexual images and other offensive material via the Internet; and

- It can also involve directing others to, or coordinating, the abuse of children online.

Signs of Online Grooming

The majority of children who are online are not being abused and never will be. The following activities could be perfectly innocent, but it is worth being alert to potential signs:

- Becoming secretive with their phone or computer

- Excessive use of their phone or computer

- Showing aggression if asked about their online use

- Change in the use of sexual language

- Unexplained gifts or cash.

Changes in childrens behaviour may also act as indicators and these can include:

- A change in your child’s self-esteem and self-confidence

- Withdrawal from family and friends

- Difficulties at school

- An increased level of anxiety

- Sleeping and concentration difficulties

- Becoming excessively concerned with washing and cleanliness.

Indecent Images of Children

Contextual Information

There are a number of definitions of ‘Indecent Images of Children (IIOC)’ including ‘youth produced sexual imagery’, ‘sexting’, or ‘Self-Generated Indecent Images (SGII)’ to mean the sending or posting of nude or semi-nude images, videos or live streams by young people under the age of 18 online. The term ‘nudes’ is used as it is most commonly recognised by young people and more appropriately covers all types of image sharing incidents.

These images are then shared via social media, gaming platforms, chat apps or forums. It could also involve sharing between devices via services like Apple’s AirDrop which works offline with other young people and/or adults, including with people they may not even know.

The content can vary, from images of partial nudity, to sexual images or video. Young people are not always aware that these are in effect images of child sexual abuse and that it is illegal. The widespread use of smart phones has made the practice much more common and the taking of such photographs is often as a result of children and young people taking risks and pushing boundaries as they become more sexually and socially aware.

A factor that appears to drive the creation of self-taken images is children and young people’s natural propensity to take risks and experiment with their developing sexuality. This is linked to, and facilitated by, the global escalation in the use of the internet, multimedia devices and social networking sites.

The reasons why children and young people post sexual images of themselves will vary from child to child. A child would not usually be in possession or be distributing these images because they have an inappropriate sexual interest in children – rather in the majority of cases, it will be as a result of teenage sexual development combined with risk- taking behaviour.

Some self-taken indecent images will be as a result of grooming and facilitation by adult offenders. See Section 4.2, Responses to Adults Involved in Online Sexual Abuse of Children.

Responses to Young People who Post Self-taken Indecent Images

A safeguarding approach is at the heart of any intervention. Parents and carers should be involved at an early stage unless informing them will put the child or young person at risk of harm.

When it is believed young people have viewed abusive images of children, consideration needs to be given to the possibility of the young person being influenced by external experiences (e.g. their own experiences of abuse, prolonged exposure to abusive material by an adult, young person is being groomed etc). Some young people will be at higher risk of developing paraphilic behaviour (a condition in which a person’s sexual arousal and gratification depend on fantasising about and engaging in sexual behaviour that is atypical and extreme) as a result of being exposed to abusive images of children. A practitioner who becomes aware of such activity will need to take this seriously particularly if that young person is living in a household where there are potential victims and a child protection issue for the young person concerned.

It is also an offence under the Sexual Offences Act 2003 to cause a child to watch a sexual act.

A person 18 or over (A) commits an offence if:

- for the purpose of obtaining sexual gratification s/he intentionally causes another person (B) to watch a third person engaging in activity, or to look at an image of any person engaging in an activity.

- the activity is sexual: and

- either

- B is under 16 and A does not reasonably believe that B is 16 or over, or

- B is under 13

Once an adult / professional becomes aware of any indecent imagery they should not view the imagery unless there is a good and clear reason to do so; any decision to view should be based on professional judgement and clearly recorded.

If it is necessary to view the imagery then the Safeguarding Lead (or equivalent) should:

- never copy, print, share, store or save them; this is illegal. If this has already happened, please contact your local police for advice and to explain the circumstances

- discuss the decision with a member of the senior leadership team

- make sure viewing is undertaken by the Safeguarding Lead (or equivalent) or another member of the safeguarding team with delegated authority from the senior leadership team

- make sure viewing takes place with another member of staff present in the room, ideally a member of the senior leadership team. This staff member does not need to view the images.

- wherever possible, make sure viewing takes place on the premises, ideally in the senior leadership team’s office

- make sure wherever possible that they are viewed by a staff member of the same sex as the child or young person in the images

- record how and why the decision was made to view the imagery in the safeguarding or child protection records, including who was present, why the nudes or semi-nudes were viewed and any subsequent actions. Ensure this is signed and dated and meets any appropriate wider standards e.g. such as those set out in statutory safeguarding guidance and local authority policies and procedures.

- if any devices need to be taken and passed onto the police, the device(s) should be confiscated and the police should be called. The device should be disconnected from Wi-Fi and data, and turned off immediately to avoid imagery being removed from the device remotely through a cloud storage service. The device should be placed in a secure place, for example in a locked cupboard or safe until the police are able to come and collect it.

The College of Policing has issued a briefing note summarising likely Police action in response to youth produced sexual imagery (‘Sexting’). This has made it clear that incidents involving youth produced sexual imagery (where there are no aggravating features) should be treated primarily as a safeguarding issue rather than a criminal offence.

When the Police are involved a criminal justice response against a young person would only be considered proportionate in certain circumstances; the key issue would be if there are any aggravating factors.

First time young offenders should not usually face prosecution for such activities, instead an investigation to ensure that the young person is not at any risk and the use of established education programmes should be utilised. The Police recommendation is that these cases should be dealt with on a case by case basis, and within a wider safeguarding framework.

Young people who have shared images, or had images shared with or without their consent should be offered appropriate support including help and support with the removal of content (imagery and videos) from devices and social media.

The Criminal Justice and Courts Act (2015) introduced the offence of Revenge Porn where intimate images are shared with the intent to cause distress to the specific victim.

Where young people are voluntarily sending/sharing sexual images or content with one another the police may use the ‘outcome 21’ recording code to record that a crime has been committed but that it is not considered to be in the public interest to take criminal action against the people involved. This reduces stigma and distress for children and help to minimise the long term impact of the situation.

Education establishments may also wish to seek advice from the non-statutory Guidance Sexting in schools and colleges: Responding to incidents and safeguarding young people.

Referral and Strategy Discussion

An immediate referral to the Police and/or Children’s Social Care through the MASH if

- The incident involves an adult.

- There is reason to believe that a child or young person has been coerced, blackmailed or groomed, or there are concerns about their capacity to consent (for example, owing to special educational needs).

- What you know about the images or videos suggests the content depicts sexual acts which are unusual for the young person’s developmental stage, or are violent.

- The images involves sexual acts and any pupil in the images or videos is under 13.

- You have reason to believe a child or young person is at immediate risk of harm owing to the sharing of nudes and semi-nudes, for example, they are presenting as suicidal or self-harming.

The referral should be made on the same day as a matter of urgency. You should also contact your agency’s Safeguarding Lead.

Where there are concerns that a child may be or is likely to suffer significant harm, Children’s Social Care will convene a Strategy Discussion / Meeting involving, health, Police and other relevant agencies. See Action to be taken where a child is suffering or likely to suffer significant harm.

Due to the nature of this type of abuse and the possibility of the destruction of evidence, the referrer should first discuss their concerns with the Police and Children Social Care before raising the matter with the family. This will enable a joint decision to be made about informing the family and ensuring that the child’s welfare is safeguarded.

The Strategy Discussion/Meeting will consider:

- The safety of all children within the household, including children in the extended family or social networks with whom the alleged abuser has contact with;

- The safety of the children shown in the abusive images;

- Whether the Police will proceed with a criminal investigation, the conduct and timing of the investigation, it is worth noting that an investigation does not always conclude with a prosecution.

Responses to Adults Involved in Online Sexual Abuse of Children

As noted earlier, some self-taken indecent images will be as a result of grooming and facilitation by adult offenders. Social networking tools are also often used by perpetrators as an easy way to access children and young people for sexual abuse. The primary purpose of Police involvement in these cases should be to ensure that the potential contact with adult exploiters is properly explored. As per Police guidance, the focus of investigations should not be on the behaviour of children who have been the victims of abuse or exploitation but on the adult offenders who ‘coerce, exploit, and abuse children and young people’.

Adults who have made/taken, downloaded or distributed abusive images of children, have committed an offence under the Sexual Offences Act 2003 and a referral to the Police is always required. If the alleged abuser lives in a household with children/young people or comes into contact with children/young people through their personal, work or voluntary activities a referral to Social Care will also be required.

Also see Managing Individuals who Pose a Risk of Harm to Children Procedure.

If the alleged abuser works with or volunteers with children or is a foster carer, please refer to the Managing Allegations or Serious Concerns in Respect of any Adult who Works or Volunteers with Children Procedure.

When adults are found in possession of indecent images, partners, colleagues and friends often find it very difficult to believe and may require support.

Information should not be discussed or disclosed to any other individual, including the alleged abuser, their partner or children as it is important there is no opportunity given to the alleged abuser to destroy any evidence that may lead to the identification of victims or be of use in any criminal proceedings. There may be occasions when it is necessary to take action before any strategy meeting has taken place because the risk is time bound and needs urgent action. Similarly, it may occasionally be necessary to make an arrest without disclosing that outside of the police service to ensure offenders are not alerted.

A Strategy Discussion/Meeting should be held on arrest to consider the risk to any children with whom the alleged abuser comes in to contact both in their personal life and through work or voluntary activities. If the images include abusive images of children known to the alleged abuser including his/her own children, an urgent strategy discussion must be held on the same day with a view to commencing a Section 47 Enquiry.

Where the alleged abuser is in a position of trust, either through their work or voluntary activities, a separate strategy meeting chaired by the Local Authority Designated Officer (LADO) will need to be convened within 5 working days. Please see Managing Allegations or Serious Concerns in Respect of any Adult who Works or Volunteers with Children Procedure.

All strategy discussions/meetings will need to consider whether the threshold has been met for holding a Section 47 Enquiry, and consider if an Initial Child Protection Conference is required. A strategy discussion/meeting may also look at appropriate multi-agency interventions early in the process and seek to minimise risk. In most cases a strategy meeting rather than a discussion is likely to be needed.

The strategy discussion/meeting will need to include the Police (who are likely to take the lead in any subsequent enquiries related to criminal proceedings) Social Care and relevant Health Professionals. The strategy discussion/meeting will consider:

- The safety of all children within the household, including children in the extended family or social networks with whom the alleged abuser has contact with;

- The safety of the children shown in the abusive images;

- When the alleged abuser and their partner will be informed about the investigation, taking into account the time needed by Police to gain and exercise a warrant to seize any electronic equipment;

- Whether the Police will proceed with a criminal investigation, the conduct and timing of the investigation, it is worth noting that an investigation does not always conclude with a prosecution.

In the case of staff, volunteers and carers, the LADO discussion will also include:

- Any contact with children or young people through the course of the alleged abusers work or voluntary activities;

- Whether any action should be taken by the employer or agency.

The Police and Social Care will conduct a joint investigation. The Police investigation is likely to be lengthy, as time is needed to analyse the results of any seized equipment and it is likely that the results of this will not be known within the 45 working days timescale for completing the single assessment. However some key factors can help determine the likelihood of significant harm at an early stage, including:

- Previous history (known to Social Care for abuse or neglect);

- Previous contact abuse of children;

- Images of own children;

- Assessment of partner’s capacity to protect indicates the children’s safety is likely to be compromised;

- Absence of cooperation;

- Understanding of risk factors associated with sexual abuse;

- Known criminal lifestyle.

If any of these risk factors are present, the strategy meeting must consider if the alleged abuser should be asked to leave the home during the assessment and if not, how the risks will be managed. Often this will include the need to devise a written/working agreement to cover matters such as supervision of contact, intimate care of children, entry to children’s rooms, sleep overs etc. Safeguards need to be put into place at the start of any work until a conclusion can be reached about the child/children’s safety. Measures such as this are not sustainable in the long term and should be reviewed regularly; this would include the need for a child protection conference.

The use of digital media is not limited by local or national borders. Those undertaking an investigation must always consider the possibility of notifying agencies in other areas (or countries) of their concerns about a child or about an alleged perpetrator.

Social Care Risk Assessment of Individuals Viewing Abusive Images of Children

Social Care involvement is usually (but not always) initiated following notification from the Police about a criminal investigation with an individual caught in the possession of indecent images of children. (IIOC) Individuals who view these images do so as they have a sexual interest in children and have acted on this interest by looking at children being abused. Some individuals will go onto abuse children and others will not, however careful and holistic assessment is required.

In order to risk assess, the following questions listed below will need to be collated from either the Police enquiry or Social Care enquiries and should formulate part of, and not replace, the single assessment process:

- What is known about the nature of images (Category A-C) age, gender of children?

- What is the source of images, e.g. commercial site, home-made images, chat rooms, is there evidence of trading?

- Was any additional material seized at the property (in addition to the hard drive) e.g. disks/dvds, videos, printed images, written material, were they hidden?

- What other technology was present in the house, e.g. webcam, digital camera, video camera, games consoles?

- If children do not live within the household, was there evidence of toys or other child centred objects?

- Is there any indication children were present whilst material was being viewed or other material featuring children known to the alleged abuser?

- Is there evidence of heavy alcohol use/drug use/distributing drugs e.g. cannabis?

- Was adult pornography present as well (though adult pornography may or may not be illegal, it is still likely to be relevant to assessment)?

- How does the alleged abuser initially present her / himself, explore background history, significant life events, previous partners and children including any contact arrangements?

- Any known previous professional involvement?

- Is there a history of domestic violence or abuse?

- Is there any prior criminal history?

- How does the non-offending parent initially react to the situation, is the non-abusing parent less or more able to protect, does the couple’s relationship increase or lower risk?

- How do children in the household present themselves and/or react to the situation (bearing in mind age and development), consider each child individually, do their own circumstances increase or decrease their vulnerability?

- Who are the safer group of significant people to the children, e.g. grandparents?

- Do agencies involved with the family have any concerns?

- Any initial indicators of abuse/neglect, do parenting styles increase or lower risk?

- What are the protective factors in the situation?

- What are the children’s daily routines particularly with regard to intimate care and bedtime routines?

- What social and community support is available to the family, are they socially isolated?

- What contact does the alleged abuser have with children and young people beyond the immediate family? Consider contact with extended family and community;

- Does the alleged abuser come into contact with children or young people through their work or voluntary services?

Online Bullying

Online abuse may also include online bullying, often known as cyber-bullying. This is when a child is tormented, threatened, harassed, humiliated, embarrassed or otherwise targeted by another child using the Internet and digital technology including mobile devices. It is essentially behaviour between children, although it is possible for one victim to be bullied by many perpetrators. In any case of severe bullying (including online bullying) it may be appropriate to consider the behaviour as child abuse by another young person.

Children can engage in, or be a target of, online bullying via text / instant messaging or social networking tools such as Whatsapp and Snapchat and can include being tormented, harassed, humiliated and embarrassed by other users. This form of bullying is a growing problem in schools and other educational settings (see Cyber Bullying Advice for Head Teachers and School Staff, DfE, and Childnet Cyberbullying: understand, prevent and respond guidance for schools and practical PSHE toolkit.

Online bullying – similar to bullying in the ‘real / physical world’ – should be taken seriously by any practitioner who becomes aware of it as this can lead to serious physical harm, for example if victims turn to self-harm or suicide. All instances of online bullying should be recorded and responded to sensitively and in line with existing anti-bullying policies and procedures and if necessary concerns should be reported to the Police.

The Department for Education have also issued guidance for parents and carers on cyberbullying (see Advice for Parents and Carers on cyberbullying, DfE).

Online Extremism and Radicalisation

Radical and extremist groups use social media as a way of attracting and drawing in children and young people to their particular cause; this is similar to the grooming processes and exploits the same vulnerabilities. The groups concerned include those linked to extreme Islamist, or Far Right/Neo Nazi ideologies, various paramilitary groups, extremist Animal Rights groups and others who justify political, religious, sexist or racist violence.

A common feature of radicalisation is that the child or young person does not recognise the exploitative nature of what is happening and does not see themselves as a victim of grooming or exploitation.

Where there are concerns in relation to a child’s exposure to extremist materials, a number of agencies including the child’s school may be able to provide advice and support. In accordance with the government’s Prevent Duty, schools and statutory agencies are required to identify a PREVENT Lead who is the lead for safeguarding in relation to protecting individuals from radicalisation and involvement in terrorism.

Suspected online terrorist material can be reported through www.gov.uk/report-terrorism. Reports can be made anonymously although practitioners should not do so as they must follow the procedures for professionals.

If a child or adult is recognised as being at risk to radicalisation a referral can be made to CHANNEL panel

See also Supporting Children and Young people vulnerable to Violent Extremism Procedure.

Content of concern can also be reported directly to social media platforms – see Safety features on Social Networks.

Harmful online challenges and online hoaxes

Carefully consider whether an online challenge or scare story is a hoax. Generally speaking, naming an online hoax and providing direct warnings is not helpful. Concerns are often fuelled by unhelpful publicity, usually generated on social media, and may not be based on confirmed or factual occurrences or any real risk to children and young people. There have been examples of hoaxes where much of the content was created by those responding to the story being reported, needlessly increasing children and young people’s exposure to distressing content.

Evidence from Childline shows that, following viral online hoaxes, children and young people often seek support after witnessing harmful and distressing content that has been highlighted, or directly shown to them (often with the best of intentions), by parents, carers, schools and other bodies

Is it a real online challenge that might cause harm to children and young people?

An online challenge will generally involve users recording themselves taking a challenge and then distributing the resulting video through social media sites, often inspiring or daring others to repeat the challenge. Whilst many will be safe and fun, others can be potentially harmful and even life threatening.

If you are confident children and young people are aware of, and engaged in, a real challenge that may be putting them at risk of harm, then it would be appropriate for this to be directly addressed. Carefully consider how best to do this. It may be appropriate to offer focussed support to a particular age group or individual children at risk. Remember, even with real challenges, many children and young people may not have seen it and may not be aware of it. You must carefully weigh up the benefits of institution-wide highlighting of the potential harms related to a challenge against needlessly increasing children and young people’s exposure to it.

Online challenge or online hoax, some principles remain the same

You should avoid sharing upsetting or scary content to show children and young people what they “might” see online. Exposing children and young people (many of whom will not be aware of or have seen the online challenge or hoax) in your institution to upsetting or scary content will be counterproductive and potentially harmful. If you do feel it is necessary to directly address an issue, this can be achieved without exposing children and young people to scary or distressing content.

Whatever the response, ask:

- is it factual?

- is it proportional to the actual (or perceived) risk?

- is it helpful?

- is it age and stage of development appropriate?

- is it supportive?

Helpful messages to share with parents and carers include encouraging them to focus on positive and empowering online behaviours with their children, such as critical thinking, how and where to report concerns about harmful content and how to block content and users.

When dealing with harmful online challenges and viral online hoaxes, there can be an added pressure from parents and carers for schools and colleges to directly address concerns. Professionals need to consider how best to manage these anxieties, and reassure concerned parents and carers, whilst not making a situation worse.

It’s important that, as an organisation with a duty to safeguard the welfare of the children and young people in your care, you only share accurate information

If a child raises concerns about a harmful online challenge or online hoax directly

While acknowledging it, if it has been raised directly, avoid overly focusing on whatever the latest harmful online challenge or online hoax might be. Focus on what good online behaviour looks like, what to do if you see something upsetting online and who and where to report it. Fact checking may help dispel myths if children and young people are identifying that they are particularly concerned that the latest online challenge or online hoax has put them or their friends at risk.

If you are worried a child or young person has been harmed, or is at risk of harm, you should report it to the local children’s social care.

Appendix 1 – Questions to support assessment

When deciding whether to involve the police and or children’s social care, consideration should be given to the following questions which will help support in determining whether a young person is at risk of harm, in which case a referral will be appropriate, whether additional information or support is needed from other agencies or whether the school can manage the incident and support the young people directly.

Do you have any concerns about the young person’s vulnerability?

Consideration should be given to whether a child or young person’s circumstances, background or sexuality makes them additionally vulnerable. This could include:

- being in care

- having special educational needs or disability

- having been a victim of abuse

- having less direct contact with parents

- lacking positive role modelling at home

Where there are wider concerns about the care and welfare of a child or young person then consideration should be given to referring to children’s social care

Why were the nudes and semi-nudes shared? Was the young person put under pressure or coerced or was consent freely given?

Children and young people’s motivations for sharing nudes and semi-nudes include flirting, developing trust in a romantic relationship, seeking attention or as a joke.

Though there are clearly risks when children or young people share images consensually, those who have been pressured to share nudes and semi-nudes are more likely to report negative consequences.

A referral should be made to the police if a child or young person has been pressured or coerced into sharing an image, or images have been shared without consent and with malicious intent.

Consideration should also be given to a child or young person’s level of maturity and the impact of any special educational needs or disability on their understanding of the situation.

Action should be taken, in accordance with the setting’s behaviour policy, with any child or young person who has pressured or coerced others into sharing nudes and semi-nudes. If this is part of pattern of behaviour then a referral to a Harmful Sexual Behaviour service should be considered.

Have the nudes and semi-nudes been shared beyond its intended recipient? Was it shared without the consent of the young person who produced the images?

The nudes and semi-nudes may have been shared initially with consent but then passed on to others. A child or young person may have shared them further with malicious intent, or they may not have had a full understanding of the potential consequences.

Consideration should also be given to a child or young person’s level of maturity and the impact of any special educational needs on their understanding of the situation.

The police should be informed through the MASH or equivalent if there was a deliberate intent to cause harm by sharing the nudes and semi-nudes or if they have been used to bully or blackmail a child or young person.

How old is the young person or young people involved?

Children under 13 are dealt with differently under the Sexual Offences Act 2003. This law makes it clear that children of this age can never legally give consent to engage in sexual activity. This applies to children who have not yet reached their 13th birthday i.e. children who are aged 12 and under.

Further action must be taken where an incident involves children under 13 and sexual acts as it is potentially indicative of a wider safeguarding or child protection concern or as being problematic sexual behaviour.

In some cases, children under 13 (and indeed older) may create nudes and semi-nudes as a result of age appropriate curiosity or risk-taking behaviour or simply due to naivety rather than any sexual intent. This is likely to be the behaviour more commonly identified within primary education settings. Some common examples could include sending pictures of their genitals to their friends as a dare or taking a photo of another child whilst getting changed for PE. Within this context, it is unlikely that police or social care involvement is required or proportionate, but DSLs will need to use their professional judgement to consider the specific context and the children involved.

Being older can give someone power in a relationship, so if there is a significant age difference it may indicate the child or young person felt under pressure to take the nudes and semi-nudes or share it.

Consideration should also be given to a child or young person’s level of maturity and the impact of any special educational needs or disability on their understanding of the situation.

If the nudes and semi-nudes are believed to contain acts which would not be expected of a child or young person of that age, it should be referred to police through the MASH or equivalent.

Did the young person send nudes and semi-nudes to more than one person?

If a child or young person is sharing nudes or semi-nudes with multiple people, this may indicate that there are other issues which they need support with such as self-esteem and low confidence or harmful sexual behaviour. Consideration should be given to their motivations for sharing.

A referral to children’s social care should be made if there are wider safeguarding concerns.

Does the young person understand the possible implications of sharing the nudes and semi-nudes?

Children and young people may produce or share nudes and semi-nudes without fully understanding the consequences of what they are doing. They may not, for example, understand how it may put them at risk or cause harm to another child or young person. They may also not understand consent.

Exploring their understanding can help in assess whether the child or young person passed on an image with deliberate intent to harm and plan an appropriate response.

Are there additional concerns if the parents or carers are informed?

Parents or carers should be informed of incidents of this nature unless there is good reason to believe that informing them will put the young person at risk. This may be due to concerns about parental abuse or cultural or religious factors which would affect how they or their community would respond.

If a child or young person highlights concerns about involvement of their parents or carers, then the DSL (or equivalent) should use their professional judgment about whether it is appropriate to involve them and at what stage. If the education setting chooses not to involve a parent or carer they must clearly record the reasons for not doing so.

Where possible, children and young people should be supported to speak with their parents or carers themselves about the concerns.

Appendix 2: Resources & Weblinks

Local Resources

Professional boundaries in relation to your personal internet use and social networking online

Personal boundaries, internet use and social networking online for foster carers

The Online Safeguarding group have also produced an Online Safeguarding Self-audit Tool which helps organisations to evaluate and manage risks, strengths and weaknesses relating to e-safety.

A number of leaflets have been produced to help inform children, young people, parents and families with the dangers online including;

When Texting Goes Wrong – The dangers of Sexting

Cambridgeshire Education ICT Service (theictservice.org.uk/)

E2BN (https://www.e2bn.org/cms/

National Resources

Harmful online challenges and online hoaxes – gov.uk

Safeguarding Children and Protecting Professionals in Early Years Settings – for Managers

Safeguarding Children and Protecting Professionals in Early Years Settings – for Practitioners

What’s the problem? A guide for parents of children and young people who have got in trouble online – by the Lucy Faithful Foundation

Child Safety Online – a Practical Guide for Parents and Carers whose Children are using Social Media

Sexting in schools and colleges: Responding to incidents and safeguarding young people (2016)

Internet Watch Foundation (www.iwf.org.uk/) – the UK hotline for reporting criminal online content

Child Exploitation and Online Protection Agency (CEOP) (ceop.police.uk/) – protecting children from sexual abuse and making the internet a safer place

Think You Know (www.thinkuknow.co.uk/) – Internet, mobile phone and technology safety for children and young people

Stop it Now (www.stopitnow.org.uk/) – confidential helpline for anyone who has concerns that someone they know may be abusing a child. Also offers support and advice to those are concerned about their own thoughts and behaviours towards children. Telephone 0808 1000 900.

Lucy Faithful Foundation (www.lucyfaithfull.org.uk/) – expertise in this area and can conduct assessment as part of a service level agreement.

NSPCC (www.nspcc.org.uk/)

Childnet International (www.childnet.com/) – includes the resources from KnowITAll (www.childnet.com/resources/kia/)

UK Safer Internet centre (https://www.saferinternet.org.uk/)

Professionals Online Safety Helpline (www.saferinternet.org.uk/professionals-online-safety-helpline) – Supporting all professionals working with children and young people including teachers, social workers, doctors, police, coaches, foster carers, youth workers with concerns regarding online safety issues. Telephone 0344 381 4772

Pan-European Game Information service (www.pegi.info) – A resource available to professionals working with children and young people, parents or carers to help determine the correct age of games

The Parent Zone (www.theparentzone.co.uk/) – parenting in the digital age

Appendix 3. Further Information and Legislation

Coram Children’s Legal Centre – LawStuff is run by Coram Children’s Legal Centre and gives free legal information to young people on a range of different issues. See Children’s rights in the digital world in particular.

See Sexting Advice for Parents (NSPCC), UK Safer Internet website and CEOP, thinkUknow website and Childnet Advice on Sexting.

Behaviour that is illegal if committed offline is also illegal if committed online. It is recommended that legal advice is sought in the event of an online issue or situation. There are a number of pieces of legislation that may apply including:

Computer Misuse Act 1990 – This Act makes it an offence to:

- Erase or amend data or programs without authority;

- Obtain unauthorised access to a computer;

- “Eavesdrop” on a computer;

- Make unauthorised use of computer time or facilities;

- Maliciously corrupt or erase data or programs;

- Deny access to authorised users.

Data Protection Act 1998 – This protects the rights and privacy of individual’s data. To comply with the law, information about individuals must be collected and used fairly, stored safely and securely and not disclosed to any third party unlawfully.

The Act states that person data must be:

- Fairly and lawfully processed;

- Processed for limited purposes;

- Adequate, relevant and not excessive;

- Accurate;

- Not kept longer than necessary;

- Processed in accordance with the data subject’s rights;

- Secure;

- Not transferred to other countries without adequate protection.

Freedom of Information Act 2000 – The Freedom of Information Act gives individuals the right to request information held by public authorities. All public authorities and companies wholly owned by public authorities have obligations under the Freedom of Information Act. When responding to requests, they have to follow a number of set procedures.

Communications Act 2003 – Sending by means of the Internet a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character; or sending a false message by means of or persistently making use of the Internet for the purpose of causing annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety is guilty of an offence liable, on conviction, to imprisonment. This wording is important because an offence is complete as soon as the message has been sent: there is no need to prove any intent or purpose.

Malicious Communications Act 1988 – It is an offence to send an indecent, offensive, or threatening letter, electronic communication or other article to another person.

Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act 2000 – It is an offence for any person to intentionally and without lawful authority intercept any communication. Monitoring or keeping a record of any form of electronic communications is permitted, in order to:

- Establish the facts;

- Ascertain compliance with regulatory or self-regulatory practices or procedures;

- Demonstrate standards, which are or ought to be achieved by persons using the system;

- Investigate or detect unauthorised use of the communications system;

- Prevent or detect crime or in the interests of national security;

- Ensure the effective operation of the system;

- Monitoring but not recording is also permissible in order to:

- Ascertain whether the communication is business or personal;

- Protect or support help line staff.

- The school reserves the right to monitor its systems and communications in line with its rights under this act.

Telecommunications Act 1984 – It is an offence to send a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character. It is also an offence to send a message that is intended to cause annoyance, inconvenience or needless anxiety to another that the sender knows to be false.

Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 – This defines a criminal offence of intentional harassment, which covers all forms of harassment, including sexual. A person is guilty of an offence if, with intent to cause a person harassment, alarm or distress, they:

- Use threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, or disorderly behaviour; or

- Display any writing, sign or other visible representation, which is threatening, abusive or insulting, thereby causing that or another person harassment, alarm or distress.

Criminal Justice and Courts Act (2015) – has created a new statutory offence of ‘disclosing private sexual photographs and films with intent to cause distress’ which seeks to address the problem of ‘revenge porn’. The rise of incidents of intimate images being posted online without consent has become a serious concern due to the increasingly prevalent culture of ‘sexting’ and the technological advances which have made it easy to reproduce and distribute photographs and videos online. This has become a particular problem amongst young adults and teenagers. Under s.33 it is offence to disclose a private sexual photograph or film if the disclosure is made without consent and with the intention of causing distress

Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 – This Act makes it a criminal offence to threaten people because of their faith, or to stir up religious hatred by displaying, publishing or distributing written material which is threatening. Other laws already protect people from threats based on their race, nationality or ethnic background.

Protection from Harassment Act 1997 – A person must not pursue a course of conduct, which amounts to harassment of another, and which he knows or ought to know amounts to harassment of the other. A person whose course of conduct causes another to fear, on at least two occasions, that violence will be used against him is guilty of an offence if he knows or ought to know that his course of conduct will cause the other so to fear on each of those occasions.

Public Order Act 1986 – This Act makes it a criminal offence to stir up racial hatred by displaying, publishing or distributing written material which is threatening. Like the Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 it also makes the possession of inflammatory material with a view of releasing it a criminal offence.

Obscene Publications Act 1959 and 1964 – Publishing an “obscene” article is a criminal offence. Publishing includes electronic transmission.

The Education and Inspections Act 2006 – Empowers school Headteachers, to such extent as is reasonable, to regulate the behaviour of students / pupils when they are off the school site and empowers members of staff to impose disciplinary penalties for inappropriate behaviour.

Protection of Children Act 1978 – It is an offence to take, permit to be taken, make, possess, show, distribute or advertise indecent images of children in the United Kingdom. A child for these purposes is a anyone under the age of 18. Viewing an indecent image of a child on your computer means that you have made a digital image. An image of a child also covers pseudo-photographs (digitally collated or otherwise). A person convicted of such an offence may face up to 10 years in prison.

Sexual Offences Act 2003 – The offence of grooming is committed if you are over 18 and have communicated with a child under 16 on one occasion (including by phone or using the Internet) it is an offence to meet them or travel to meet them anywhere in the world with the intention of committing a sexual offence. Causing a child under 16 to watch a sexual act is illegal, including looking at images such as videos, photos or webcams, for your own gratification. It is also an offence for a person in a position of trust to engage in sexual activity with any person under 18, with whom they are in a position of trust. (Typically, teachers, social workers, health professionals, connexions staff fall in this category of trust). Any sexual intercourse with a child under the age of 13 commits the offence of rape.

Serious Crime Act 2015 – The Act introduces a new offence of sexual communication with a child. This would criminalise an adult who communicates with a child for the purpose of obtaining sexual gratification, where the communication is sexual or if it is intended to elicit from the child a communication which is sexual and the adult reasonably believes the child to be under 16.

Appendix 4 – Keeping Children Safe in Education 2020 – Annex C: Online safety